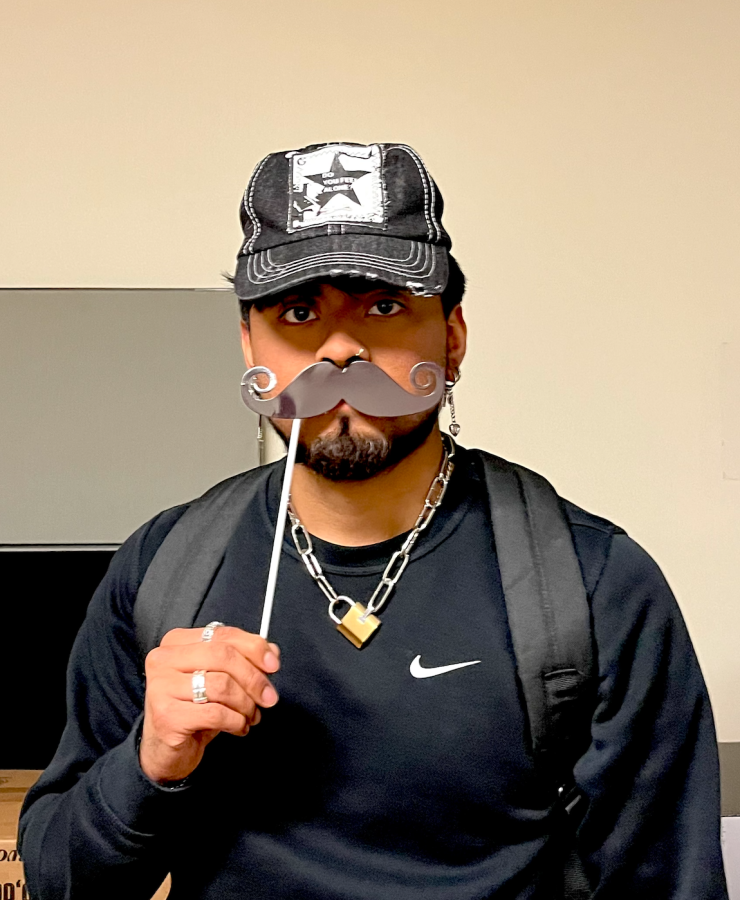

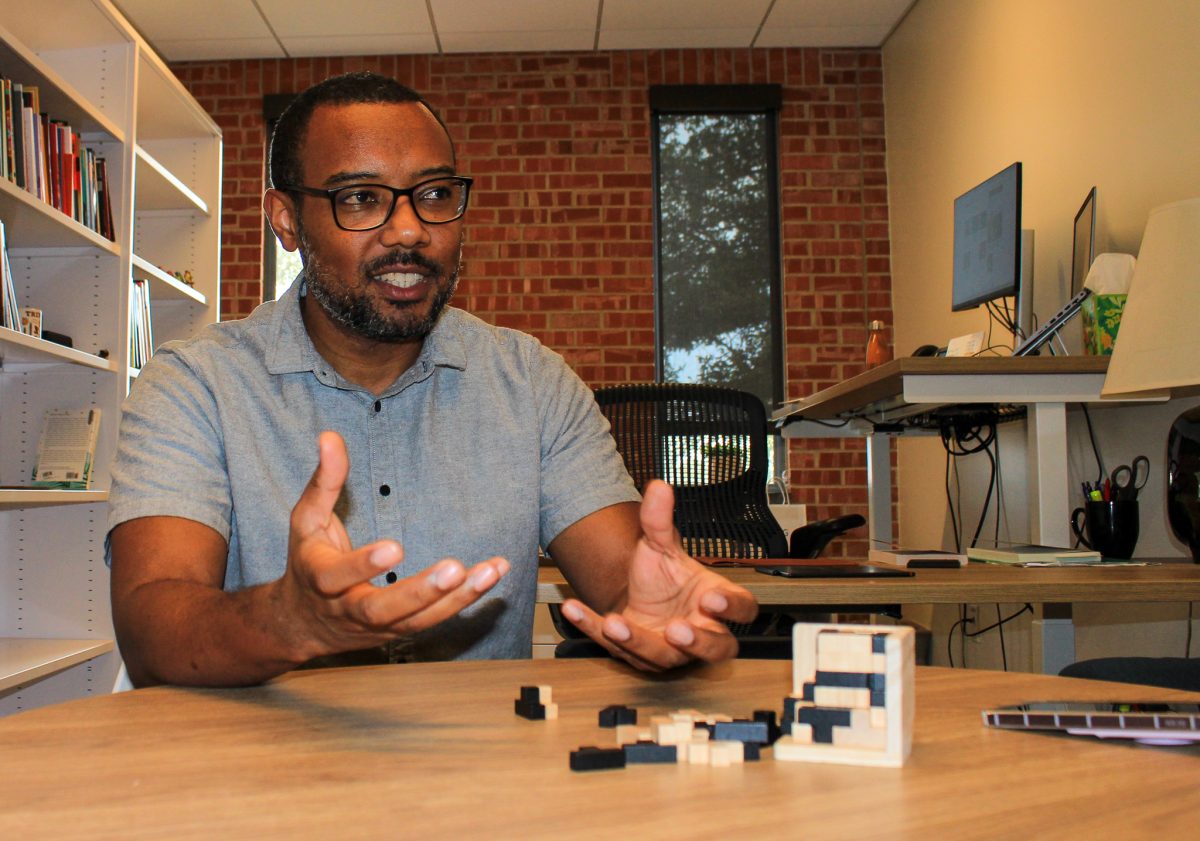

Photo by Mona Mirpour

Jackpot is a series in which we highlight a variety of students and their interesting lives. Every story highlights a different student, whom we’ve selected at random. This week, we talked to Casey Fernhout, a sophomore political science major and aspiring veterinarian who opened up about her mental health.

When sophomore Casey Fernhout was in first grade, her YMCA counselor passed away from cancer. As any child would, she felt sad. She grieved. But Fernhout had always been a little different, she said, and this introduction to death took hold of her differently, too.

The loss manifested itself in her anxiety. She began to think about life and death constantly, long after her counselor passed away.

“I have to say that it was almost like I was going through a grieving process,” Fernhout said. “Like I was grieving the loss of someone I had yet to really lose. There was that YMCA worker, but I don’t even remember his name. I would grieve the loss of family members who probably aren’t going to die, God willing, for another 20, 30, 40 years. Then I would cry for my own impending doom, and I would just grieve that loss.”

Fernhout has struggled with anxiety, social anxiety, bouts of obsessive-compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder throughout her life. When she was younger, she was put on antipsychotics because she was hearing voices in her head.

In reality, Fernhout just had overwhelming worries. As other six-year-olds were running around and playing with friends, her antipsychotics made her sleep too often, and she continued having her existential thoughts.

“People always said I was a deep thinker, but I was just a kid with a bunch of worries,” Fernhout said. “Like, what’s the meaning of life? What’s the purpose of life? What’s after death? I could think about it ’til I was crazy.”

Now, Fernhout is on medication that slows her thoughts down and makes the anxiety easier to cope with. She is a political science major, vice president of Animal Welfare, a member of TU Secular Alliance and a shadow of current Eco Allies officers, planning to become one when a position opens up. Fernhout said keeping busy helps her cope, as she feels like she is doing something with her time and giving purpose to her life.

This summer, however, was a different story. She said she had ignored the signs that something was wrong with her medication, and once she had nothing to occupy herself with, her mental health declined.

“Let’s say we go from college life where we always have an appointment with someone. We always have to be somewhere. We always have to get something done until summer vacation, where it’s just me,” Fernhout said. “Nobody’s telling me what to do. Nobody’s saying I have to do something. I just watch the clock go by, and that causes a lot of stress for me.”

After Fernhout got back on track with her medication this summer, she was able to shadow her family’s veterinarian to give her experience in a field she wants to enter in the future. After Trinity, she wants to go to veterinary school with an end goal of being a conservation veterinarian, a career that will always give her something to do. Something to contribute. Something to focus on.

“I’ve always been pretty ambitious with things like that,” Fernhout said. “I’ve always wanted to do something that had a lot of meaning. I never wanted to work at a desk job. For some people, that works, and they’re fine with it. They’re happy with it, but for me, I would just fall into a deep depression. My philosophy in life is that the purpose of life is just to leave some positive impact, whether it be something small or something big.”

Fernhout has already begun her positive impact on the world, notably a book she wrote her senior year of high school. As part of her Independent Study Mentorship class, she worked with James Roberts, a retired Trinity neuroscience professor, to research the stigma surrounding mental health.

Naming bipolar disorder and schizophrenia as examples of the mental health conditions she researched, Fernhout said writing the book helped her realize the stigma with which she regarded her own mental health. From a young age, she remembers experiencing stigma firsthand.

“I never really fit in,” Fernhout said. “I don’t think anybody did when they were going through puberty, but just the way I was, the way I acted, the way I did things was a bit more odd than most kids. I was obsessive with some things. For example, I would draw the same thing over and over in middle school. Of course, I got bullied for it. I even got bullied by some of the teachers for it because it was such a weird thing to do. But now, I think it’s just me.”

Despite all of her struggles with anxiety and its effects on her life, Fernhout is determined to rise above by taking care of herself and finding purpose in her life.

The thoughts about life and death remain, she said, but she is coping like never before.

“Currently, the person I am now with the medicine I take, I am happy, I enjoy life, I have meaning, and I really just am taking it step by step, a day at a time.”