O’Neil Ford’s architecture “guided by the hills”

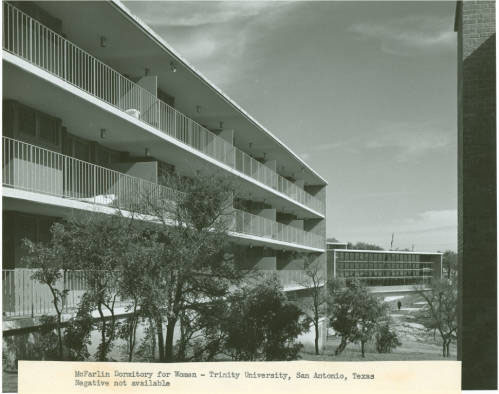

McFarlin Dormitory for Women Exterior View. c. 1955. 98-18-019, Trinity University History, Coates Library Special Collections & Archives, Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas.

I remember only a brief part of my first Trinity tour. My tour guide stopped outside of Storch Memorial Library—we faced the San Antonio skyline with our backs to the academic buildings.

The tour guide then proceeded to say something along the lines of how Trinity’s campus was strategically planned. From this spot, our attention was drawn to the view of the skyline, which as the tour guide explained, reminds students what their future entails and that what they do in the “real world” matters.

This may have been a line fed to tour guides by the Admissions Office, but it definitely caught my attention. Trinity’s campus is special, intricately planned, and worth learning more about.

At the time of Trinity’s Skyline Campus debut, Trinity was “…one of the most innovative and thoughtfully-designed college campuses ever created in the United States,” said Kathryn O’Rourke, professor of art history and director of the minor in architectural studies. By understanding the concepts and methods behind campus architecture, we can begin to appreciate them more.

There is a small but important difference between buildings (walls and a roof providing shelter) and architecture. Understanding this difference is vital to understanding what makes Trinity architecture a form of art.

Architecture conveys ideas. These ideas, however, may not be as concretely presented as ideas communicated through reading or attending a class lecture.

O’Neil Ford was the notable Texas architect in charge of designing Trinity’s skyline campus from 1949 to his death in 1982. Ford’s architecture on campus explored many ideas. Some of those include integrity, a consideration and connection to nature, and the fostering of a community.

These ideas led Ford to build in a way separate from established methods of building at the time. As Ford explained in his 1967 commencement speech at Trinity University (where he was awarded an honorary doctorate of fine arts), “…the freedom to be different and have different thoughts extends to planning and building differently and without the fetters of rigid restrictions or preconceived notions.”

Integrity in architecture refers, in the simplest terms, to the exterior appearance of a building coinciding with the building’s interior functions. This idea is a driving factor of functionalist modernism and has been simplified and popularized by Louis Sullivan’s signature phrase, “form follows function.”

Take Ford’s Isabel McFarlin Dormitory on the west side of campus for example. The building is horizontally split in 3 distinct segments on the exterior, demarking the three separate floors of the interior space. Each pair of windows on the exterior is situated to identify the separate rooms and bathrooms on the interior. The form of the building is true to its interior function.

William Wurster, a leading architect at the time and a consultant for Trinity’s architecture, encouraged Ford to “let the hills design the buildings.” And that they did, along with the spatial design of the campus.

What I appreciate most about Trinity’s campus is its relationship with nature. That being said, we are to thank Ford for the dreaded trek up and down Cardiac Hill. Trinity’s campus is situated on a 107 acre abandoned rock quarry, what Ford described as “a dismal and antagonistic jungle.”

Ford explained in his 1967 commencement speech, “The buildings on this beautiful ex-dump heap are ranged above and below the rock-quarry bluff with enough ease and order and interrelation to make them relevant to each other and to teaching and learning and sleeping and eating and play and worship.”

The bluff provides an important separation between areas on campus: a space to work and learn and a space to relax and replenish. The stroll, speed walk, or run between upper and lower campus allows for time to reflect or simply enjoy the native landscaping that the university groundskeepers so tediously maintain.

Ever noticed (or cursed) at the lack of roads running through campus? While an inconvenience to students with disabilities or touring students attempting to navigate from Shook to Stadium Drive, the lack of interior roads on campus allows for a human-scaled space and affords us with obvious safety benefits.

The student experience on a campus without roads and with little outsiders, is understandably referred to as the “Trinity bubble.” As O’Rourke explains, “Ford very much admired the campus of the University of Virginia, which was centered on an “academical village,” that supported the image and idea of students studying in a place set apart from other kinds of places.”

Details of Trinity architecture and campus design are there for a reason and they should be appreciated—not every college student is so lucky to have had O’Neil Ford design their campus. On your next trip to campus, take the time to stop and stare—you might pick up something you never noticed was there.

My name is Ashley Allen and I am a senior completing a BA in art history at Trinity University, with a minor in Medieval and renaissance Studies. I hope...

Steve Bartels • Feb 5, 2021 at 4:03 pm

If you’re really into it, you can check out another interesting Ford building located close to Trinity. It’s a former car dealership at 3303 Broadway. It has been repurposed several times since it was built and I think it’s vacant right now so you can walk around it and check it out. It’s cool!

Steve

Eve • Mar 13, 2024 at 4:13 pm

Hi Steve,

Do you happen to know what other local businesses he may have designed? I have heard that he was involved in the design of the HEB SA #2 that opened in 1951 at 4821 Broadway, but I’m having a very difficult time in proving that! I just looked up 3303 Broadway, and it does resemble the architecture of the Trinity dorms!

Thanks!

Mike Bacon • Feb 4, 2021 at 8:58 am

What a great piece on the beauty of this campus. Nice work and great quotes from ONF!