Not your typical scholarly publications

The works of 3 faculty members that don’t fit traditional scholarship

Professors aren’t just the really smart people who assign us seemingly impossible tasks. Trinity professors are also really smart people who have to write about things. It’s fairly easy to visualize a piece of scholarly writing, because we’ve all had to find articles to put on an annotated bibliography: they are typically verbose and often make an argumentative claim about a topic in their field.

Not all faculty publications are those long articles in tiny print. To sample the larger world of academic writing, I talked to three Trinity faculty members whose publications break our, or at least my, preconceived notions of academic writing.

Kelly Grey Carlisle has been a Trinity faculty member since 2011 and currently teaches creative writing classes.

“My main focus is creative nonfiction and always has been,” Carlisle said.

Here is Carlisle’s definition of creative nonfiction (if, like me, you’re not really sure what that phrase describes).

“Creative nonfiction is telling a factually true story as accurately as possible using techniques from what we would call imaginative writing or literary writing [in order] to make that factual story more compelling and a more interesting read.”

As a vast genre, creative nonfiction has numerous subgenres, like crime writing and memoir writing — a subgenre Carlisle has experience with. Her memoir “We Are All Shipwrecks” was published in 2017, and its publication has presented its own set of concerns for Carlisle. The potential personal nature of creative writing distances works like memoirs or personal essays from conventional scholarship.

“Knowing students may read [“We Are All Shipwrecks”] is interesting,” Carlisle said. “Writing that memoir was important enough to me that I will deal with students having read it or other personal essays of mine, and [the fact that] creative writing comes out of personal space is also a consideration when publishing non-traditional scholarship.”

Despite her works first being published years ago, Carlisle has reservations about calling herself a writer.

“There’s the stereotype of the ‘wannabe writer’ who has pretensions of being awesome, and I don’t want to be that, so I am really hesitant to call myself a writer even after having published a book and essays,” Carlisle said.

Part of this reticence might result from academia’s ambivalence toward counting creative writings as scholarship. The genre’s place in scholarship is something Carlisle faces a lot, although, “in all official universities’ dialogue and rules about creativity or creative work, those pieces are given equal weight to other professors’ scholarship. Really I often feel in day-to-day interactions that [creative nonfiction] doesn’t seem to fit in with scholarship that may be regarded as serious or intellectually rigorous or demanding as discovering [something] new,” Carlisle said. “Sometimes it is a profoundly strange place to be.”

While Carlisle writes creative nonfiction, Eva Pohler is the author of almost 40 fiction novels which span seven respective series and two main genres, supernatural mystery and young adult paranormal romance. She has been a Trinity faculty member for five years, but writing has always been a part of her life.

“I started writing when I was in middle school … but it wasn’t until around 2000 or 2001 that I started becoming a little more serious about writing and developing it as a possible career,” Pohler said. “It wasn’t until a little before I published in 2012 that I was able to turn [writing] into an actual career and not just a hobby.”

Getting her work published took some time, and it wasn’t until an agent who requested a revised manuscript lost interest in her work that Pohler decided to begin self-publishing.

“At the time, there were some people who were becoming very successful as indie authors,” Pohler said. “I was terrified to go the indie author route because I was afraid it would end any chance I had at [getting] a traditional book deal. After enough time and seeing all those people become very successful, I finally took the leap and decided to publish myself, and I have not regretted that decision for a single moment.”

Writing fiction and the creativity necessary to do so is something Pohler enjoys.

“As a reader, I always prefer fiction,” Pohler said. “From a very young age, I fell in love with fiction and wanted to create my own worlds. I realized it was such a pleasure for me to [create scenarios and scenes], and I never wanted to stop, so I still make these pretend worlds now for my readers.”

Although fiction is not always historically considered to be scholarly work, Pohler’s experience as a creative writer in academia has been a good one.

“It’s been wonderful,” Pohler said. “It’s such a beautiful coupling, especially with this opportunity I have here at Trinity to teach for the entrepreneurial department because I’ve basically designed a course for people like me. I wish this course would have been offered when I was a student here.”

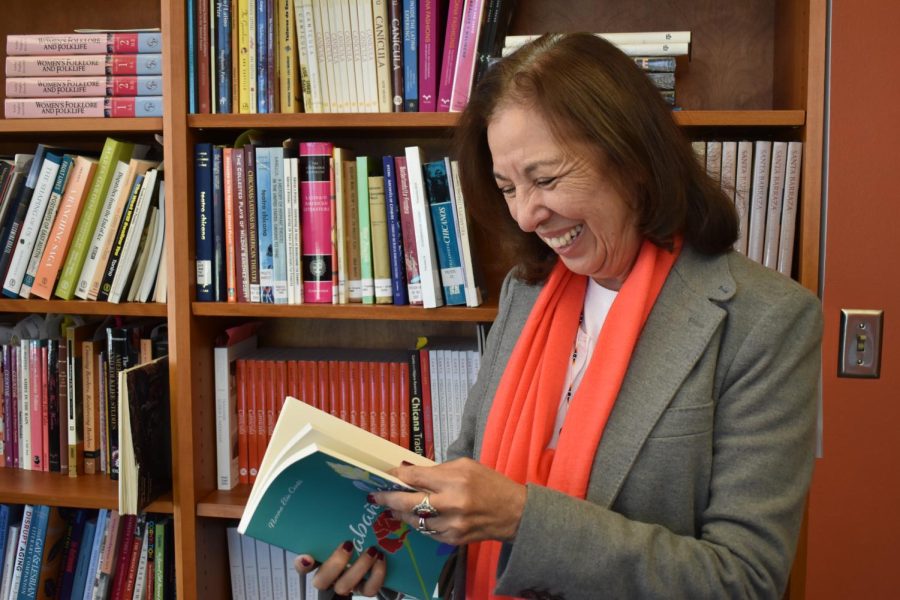

Norma Cantú’s work sits in between creative nonfiction writing — like Carlisle’s memoir — and fiction works like Pohler’s. Her novels “Canícula: Snapshots of a Girlhood en la Frontera” (1995; 2015) and “Cabañuelas” (2019) are loosely based on her own life, but they are not entirely nonfiction, as Cantú’s description of “Canícula” as a fictionalized memoir highlights. Cantú also describes “Canícula” as a creative autobioethnography: “It’s creative, which means fictionalized, autobiographical, and ethnographic.” The place of Cantú’s writing between genres and disciplines mirrors her own story growing up in la Frontera, the U.S.-Mexico border, a throughline among her works and her own story.

The ethnographic pieces of Cantú’s work comes with her being a folklorist. Her work also highlights the distinctive traits and habits of various people groups. According to Cantú, “anthropology is probably the closest [discipline to folkloristics] because we look at people, customs, traditions, myths, legends, jokes, pretty much anything that has to do with folk, with people.”

Cantú’s 2019 novel “Cabañuelas” is based on her own experiences in Spain, where she studied the culture, specifically Spanish fiestas.

“I’ve done a lot of work on cultural traditions, like quinceañeras, the coming of age tradition, on fiestas like the George Washington’s birthday one in Laredo [and] the Matachines,” Cantú said. “I am working on a book on the Camino de Santiago, which is a pilgrimage in northern Spain.”

According to Cantú, being an author of fiction within academia makes for an interesting back-and-forth.

“I also write academic papers and lectures and things like that, so it’s almost as if I turn off one and turn on the other when I’m writing a novel, working on poetry, but often they kind of come together and it’s really, I think, a magical process [of] how one informs the other,” Cantú said.

Time holds a recurring spot across Cantú’s works, both its movement and the ways it slows down as we remember. Her collection of poetry “Meditación Fronteriza: Poems of Love, Life, and Labor”— along with her novel “Canícula”— uses form and organization to chronicle the larger story of individuals living in between cultures.

My name is Ayden Smith and I am a junior studying English here at Trinity. I am from Friendswood, Texas, and grew up coming to San Antonio for little vacations....

My name is Claire Sammons and I am an Anthropology and Communications double major. I have worked for the Trinitonian since fall of 2020. I became a photographer...

Christine Mangle • Feb 19, 2022 at 6:00 am

Great article, Ayden!