A duality of worlds: The Centro de Artes’ current exhibits

Hernandez and Montelongo are sharing their Latinx experiences in the U.S. through artwork

Tapestries on display at the Centro de Artes Gallery

On the eastern corner of the Historic Market Square downtown sits the Centro de Artes, a beautiful two-story art gallery that dedicates itself to sharing the Latin American experience through Latino artists and works. Admission is free Wednesday through Sunday from 10:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., and new art installations rotate every few months. The two current exhibits are: Leila Hernandez’s “La Visa Negra 2.5: Tendiendo los Trapitos al Sol” and Elizabeth Jiménez Montelongo’s “The Euphoric Dance of the Unconquered Mind.”

After visitors sign in at the front lobby, they are ushered into the darkness of the first floor, where Hernandez’s “La Visa Negra 2.5: Tendiendo los Trapitos al Sol” awaits. Translating to “The Black Visa 2.5: Hanging the Laundry in the Sun,’’ the exhibit is an amalgam of narratives that intertwine the liminal space between two countries and their cultures. Using a wide variety of recycled materials including old quilts, tablecloths, tarps, thrift store clothes, cinder blocks and even Cheeto bags, Hernandez weaves visitors through the trials, tragedies and triumphs of the people “de la visa negra.”

As the exhibit explains, for the people who don’t have the money or the legal means, the term “Visa Negra” is the satirical codeword for the only “paperwork” necessary for crossing the Rio Grande and gaining entry into the United States.

Split into three major pieces, “La Visa Negra” starts with a piece called “Kokonetlatok” (Sleeping on the Job), which consists of paintings of children that have been lost, stolen, retained or killed trying to cross. Giving faces to those thousands of “faceless” children, it reminds visitors that many still remain in detention cells across the country.

In her second piece, “Tapestries,” Hernandez informs visitors of the meaning of the second half of the exhibition’s title, “Tendiendo los Trapitos al Sol” (Hanging Laundry in the Sun). The laundry being hung is a metaphor for the old phrase “airing one’s dirty laundry,” or discussing matters many would rather remain silent on. The tapestries interlace sewn on flowers with federales (Border Patrol), razor wire and border fences that dwarf small silhouetted figures.

The third piece, “Los Labores,” celebrates those that endure the passage of the Visa Negra to work for a better life. The entire exhibit builds layer upon layer of meaning, washing over the visitor, not unlike the currents of the Rio Grande. Located in a city where 53 migrants were found dead in a tractor-trailer in June, this timely exhibit shines a light on the experiences of many immigrants who die, suffer and resiliently survive the experience of the Visa Negra.

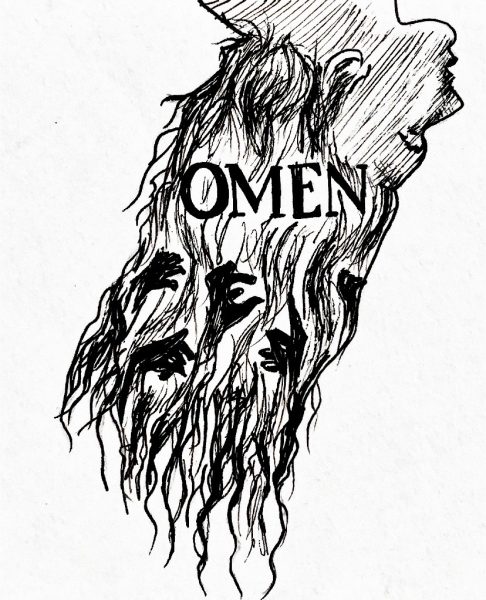

Moving upstairs to the second exhibit, visitors climb to l

ightness with Montelongo’s “The Euphoric Dance of the Unconquered Mind” featuring the eye-popping color and energy of Mexika dancers. Known eponymously with the place name of “Mexico” and colonially labeled as the “Aztecs,” the Mexika once commanded the “Aztec” empire and built the legendary city of Tenochtitlan.

In 1521, a band of a couple of hundred conquistadors in alliance with Tlaxcaltecs led by Hernán Cortés destroyed the Mexika kingdom along with the city of Tenochtitlan. At its height, the Mexikas created one of the most advanced civilizations on the planet. Five hundred years later, their people and culture still number over 1.5 million who speak the native language, Nahautl, and the countless others who hold Mexika ancestry in their blood.

In Montelongo’s paintings, we find the Mexika dancing over vibrantly colored oil paintings. No amount of written description can adequately convey the life and energy that these pieces render.

The pieces originally began as photographs of San Francisco Bay area Mexika dancers that Montelongo subsequently rendered to the canvas by “applying paint with a palette knife with a thick impasto.” Montelongo explains they were made in “acknowledgment of the living culture-keepers who preserve and practice indigenous traditions in the 21st century, across social and political borders.” The work is a celebration of “mental liberation and honors our Indigenous ancestors.”

Though the exhibits are separate works, done by separate artists with separate intentions, they work in tandem with the visitor. The curation of the two exhibits deliberately lends visitors a visceral sense of duality — with one highlighting the freedom of movement and the other highlighting the suffering from the lack thereof. It is a thoughtful and fantastic way to spend an hour in the shadow of downtown.

My name is Sam (he/him) and I'm a photographer here with the Trinitonian. I'm a senior Communications and German double major from Austin, Texas, and...