In Julia Poage’s piece, “The America I’ve Inherited,” one of her three graphic novel-style drawings exhibited in the “Mini,” she defines the phrase the ‘1.5 generation.’ This term generally refers to Holocaust studies, but she applies it to those who were alive when 9/11 happened, but were too young to fully process the violence.

“I’m applying this term to help me figure out what the 1.5 generation of the violent events that shattered 21st-century America can do to work out our collective trauma,” reads a panel in Poage’s mixed-media illustration.

This concept is abundant throughout the “Mini” exhibition, which opened last Thursday in the Michael and Noemi Neidorff Gallery. Controversy covered in last week’s issue with a point and a counterpoint highlighted that the theme of identity is at the center of Abigail Wharton’s and Ariel del Vecchio’s work, “Constructed Religiosity.”

But I found recurring themes of identity in all of the works featured, which totaled seven works done by nine artists. In Erina Coffey and Dinda Lehrmann’s piece “Color: A Series on Diversity,” digital photography, textiles and paint chips were mixed to produce a work that comments on race. “The focus of this work is to highlight race issues as well as to appreciate the beauty of different skin tones,” Coffey and Lehrmann wrote in their artist’s statement.

The photography of this piece is beautiful and warm, focusing on close-ups of skin, which avoid being tantalizing by focusing on the humanity, rather than the objectivity, of skin. However, I felt the emotional crux of this piece came from the collected pile of skin-colored cloth on the floor. The whole piece certainly emphasizes shared humanity, but there is a celebration of differences in the patchwork cloth, which pours out of the wall in a way that could almost seem accidental or reductive in another work.

Likewise, Elizabeth Day’s work, “Landscapes,” builds a dichotomy between bodies and the world outside them, though this time with literal outdoor landscapes. In black and white photographs, Day pairs places on the body with those of external places, both familiar, but not entirely distinguishable from her photographs. The body parts appear larger than they would be in real life and the landscapes smaller, making a collage of skin and sky that seems to be just one.

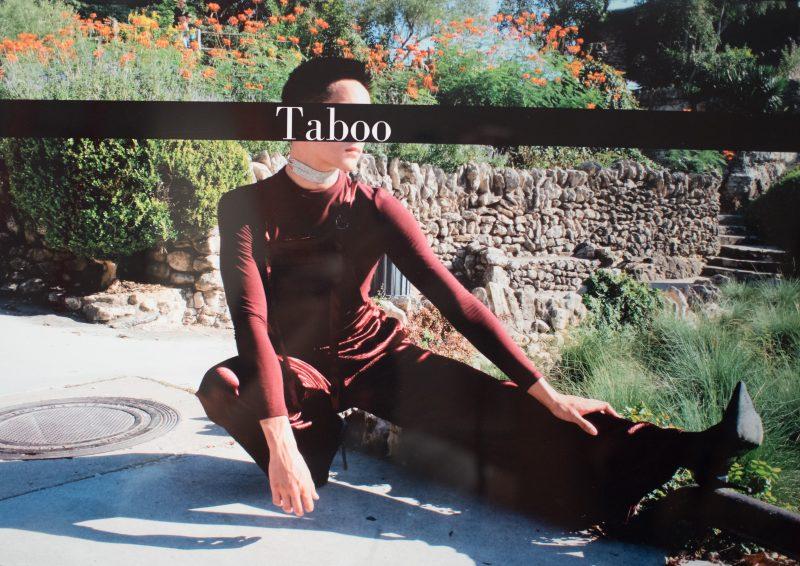

Alex Motter and Quinn Bender’s piece tackles the connection between our physical selves and our identities through the lens of fashion, specifically men wearing chokers. Motter said he was inspired to create this piece after an incident where someone said something homophobic to him while he was wearing a choker. The idea of generations comes up as Motter discusses the different aesthetics in the images, each representing a different time period in history, meant to communicate how gender norms change over time.

The art I viewed all shared a common thread of changing perspectives through art, especially Kristina Reinis’ “What Agonizing Fondness,” which feels like a literal exploration through the effects of grief. “I look at the intrinsic desire to to preserve memories after the death of a loved one,” reads Reinis’ artist statement. The melancholic colors of this piece, created using the pigments of flowers, transform a desk landscape into an expression of grief.

Scattered throughout the gallery, Raquel Belden’s work “Radiator Child” encompasses the juxtaposition I noticed in the other pieces. “‘Radiator Child’ explores the disjuncture between outward presentation and inner sentiment of the individual,” reads Belden’s artist statement.

On their own, these small paper children are an unsettling representation of inner tension and distress. Within the larger context of this year’s exhibit, the radiator children in Belden’s work help to communicate the idea, addressed specifically in other pieces, that there is harmony and dissonance created by the juncture of ourselves and our identity, and both should be explored in art.