One of the great values of art, film, photography and literature is that they are our only means, outside of direct experience, of grasping and confronting the reality of war, history and ideology. Videogames are often thought to lack this property by a public for whom “videogame” conjures images of Mario or machine gun fire. This is understandable, but mistaken — and I like Mario and shooters.

In the hands of skilled and serious developers, videogames can offer immersive and accurate accounts of the depravities of the human condition that, due to their unique inclusion of player choice, can meet or exceed art, film, photography and literature.

For this potential to be realized, though, players must shift their expectations and play games with a mature outlook, taking their choices seriously. Two games serve as good examples.

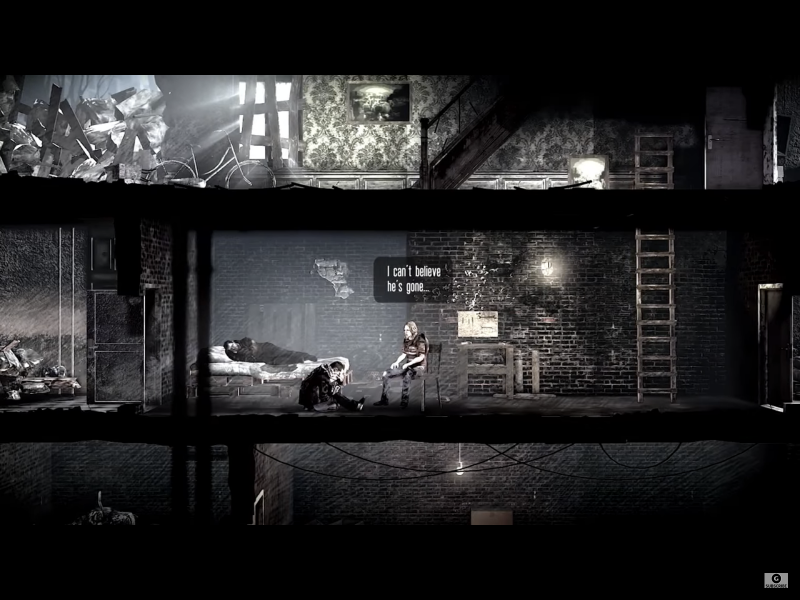

First, “This War of Mine,” a survival-strategy game inspired by accounts of the civilian experience of the Siege of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War. The player controls a small number of civilian characters inside an abandoned house. Each character has a face, a name and a backstory. If they are sick or hungry or tired, they will stumble about, sad and unproductive. During the day, sniper fire traps the civilians indoors.

The player can choose what the characters do, but that choice is informed by constant, acute, wrenching scarcity. Do you use a piece of raw meat to feed one of your starving characters or use it to set a trap for a larger animal and hope that the trap will yield more food soon?

An unforgettable moment occurred in the game for me when, due to a winter chill, all my characters were severely sick and in desperate need of medicine. My only option was to scavenge the house of an elderly couple. Opening the door, the old man begged me not to hurt him or his ailing wife. He didn’t attack when I began pilfering his belongings, merely asked me why plaintively.

When I approached the medicine cabinet, he begged me to leave some medication for his wife. I needed it for my characters, though, and I took it. Returning to my characters with the medicine, all I felt was a kind of numb revulsion, a hollow feeling in the pit of my stomach that stuck with me, a kind of guilt. That’s what player choice and good design can do: make real the brutality of war.

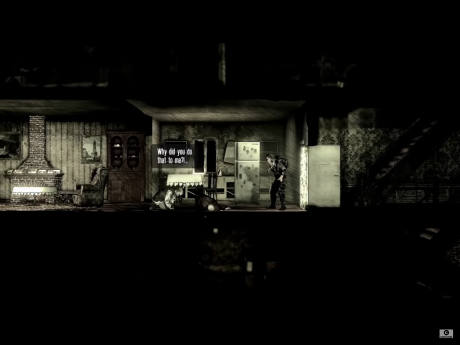

Next, consider “Fallout: New Vegas,” an open-world game set 200 years after a nuclear war in Las Vegas and the Mojave Desert. The player’s character, a courier, stumbles into a conflict between several factions in conflict over the Hoover Dam.

From the west, there is the New California Republic (NCR), a sprawling, bureaucratic government similar to the pre-war United States. The NCR has a standing army and offers protection from raiders but it’s overextended, ignores the desire for independence of the towns it occupies and suffers from crony capitalism.

From the east, there is Caesar’s Legion, a vast army of tribes who have been crushed and unified under Caesar, a man who styles himself on the Roman emperor. The Legion is brutal and socially regressive, but driven and purposeful in a way that the NCR is not.

Alternatively, the city of New Vegas itself is controlled by Mr. House, a pre-war tech genius who has kept himself alive and wants to carve out New Vegas for himself with an army of robots. He speaks grandiosely of restoring civilization and achieving space travel within 50 years.

Alternatively, the player can overthrow all three factions and secure New Vegas for themselves. No faction is perfect; each reflects distinct philosophies and notions of government. Each has substantial flaws and substantial promise, with no clear ability to predict which would lead to a better future.

Above all, though, the factions feel real, not concerned with battles for good and evil but for control of the logistical advantage of Hoover Dam, like real nation-states. The player must choose which faction to side with, expressing and enacting their values in the process.

“Fallout: New Vegas” also has four expansions in which the player is compellingly presented with and must choose how to address problems of human greed, cultural innocence, tribal warfare, unrestrained scientific research, the persistence of history and the power of the individual to shape it and the use of nuclear weapons.

These two games, a small fraction of the examples I could have used, demonstrate the potential of the medium, though that potential is dependent upon the maturity of the players.

To play “This War of Mine” with a mindset of learning the game mechanics well enough to ‘win’ by acquiring abundant resources would miss the point. To play “Fallout: New Vegas” with the mindset of acquiring the biggest guns and the most money would likewise miss the point.

To truly appreciate games, the choices available within them need to be taken seriously.