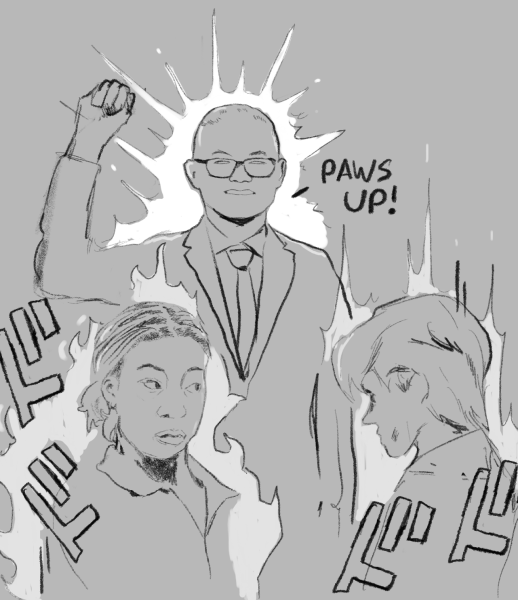

Trinity gains new momentum: Vanessa Beasley arrives

Trinity’s 20th president’s first steps on campus come with other historic firsts

Before she had ever dreamed of being the president of Trinity University, Vanessa Beasley stood in front of Vanderbilt University’s first-year housing with two suitcases in hand. She had just driven 10 hours to get there with two other new students. She was a first-generation student, one whom her family hoped would go to law school.

Just two weeks ago, Beasley stood in front of Trinity’s first-year housing as new students and their families flocked to campus from far and wide. As they began their own college journeys with their own suitcases and boxes and carts full of dorm decor, she welcomed them in.

Although now far from her first year of college, Beasley is still experiencing firsts. Her first job back in Texas after working at Vanderbilt. The first female president in Trinity’s history. The first president to start at Trinity now that it has entered the rank of National Liberal Arts University.

On top of that, Beasley has admired Trinity from afar ever since her son toured the campus in 2014.

“I could see faculty interacting with students and I could see a level of engagement that, frankly, as a parent and an educator, just seemed remarkable to me,” Beasley said. “[It] literally set the standard for all the other visits that we did.”

Beasley describes herself as student-centered. She plans to visit alumni chapters around the country and has conducted focus groups with faculty and staff, but she said she strives to be in tune with the students. On the first day of class, she attended a Creative Genius First Year Experience (FYE) class taught by Jacob Tingle, assistant professor of business administration.

“I could’ve stayed there,” Beasley said with a smile on her face. “I could’ve just…yeah. I’ve got too much to do to go every day, but man, that class sounds great.”

Looking around the room that morning, she said she thought about her own first college class. The thoughts that zoomed through her head. Was she wearing the right clothes? Would she ever make friends?

“I love working with first-year students in particular because I did not have an easy transition from high school to college,” Beasley said. “I just believe strongly in that idea that you should make it better for the people who follow you.”

Beasley was raised by her mother, who didn’t have a college degree. After Beasley had gone to college, her mother would go on to earn not only an associate degree but a bachelor’s and a master’s as well. However, when it was time for Beasley’s first year at Vanderbilt, there was knowledge that seemed to be missing.

“I don’t think she could take time off work to take me [to move in], but I also think she didn’t know parents were supposed to,” Beasley said. “Sometimes for first-generation students, and their families, it can feel like there’s an invisible guidebook or there are invisible rules that nobody tells you.”

Now, as an administrator, Beasley said she rejects the notion that a research-focused university like Trinity must choose either to value research or student experience. In other words, valuing a rigorous education and research doesn’t exclude students who aren’t sure how they fit.

“It’s important, and in fact essential, to be able to say that doesn’t mean students come second,” Beasley said. “That means we invite students into those spaces, and we invite all students into those spaces. Not because you know somebody who knew somebody who got you the internship with your cousin. Not because you have a network. In fact, first-generation students having that access is really, really important.”

Beasley enters Trinity’s community at a time she calls momentous. Part of this momentum is being the first female president of the university, something she said reflects well on the Trinity’s Board of Trustees, who led the presidential search.

“What it meant to me was our Board of Trustees had recognized my experience, my achievements and my commitments from the past and said, ‘we entrust you with this great responsibility,’” Beasley said. “They could’ve said that to a man, too. We know, just from past historic and social practices, it’s usually men who have been given that kind of trust.”

This momentum is also related to the recent reclassification of Trinity as a National Liberal Arts University and the anticipation associated with that ranking. Although any ranking will be cause for celebration, she said there’s a “moonshot dream” of ranking in the top 25.

“I did some research on that group, on the top 25, and it’s very interesting how many of the top 25 are led by women,” Beasley said. “I don’t have a conclusion or a hypothesis there, but it’s fascinating.”

Aside from national rankings, Beasley sees opportunity in the ways in which Trinity is involved with San Antonio and the region, a relationship that must be sustained, engaged and authentic. According to Beasley, she wants to prepare students to be residents of San Antonio, too. In her view, a great city benefits from a great university.

“We need art. We need music. We need poets,” Beasley said. “If we turn to a society that’s just technical knowledge, we’ll lose what it means to be human, and that’s one of the things a great university does.”

When asked if she came in with ideas to change ongoing strategic plans, Beasley shook her head.

“Nothing’s broken here,” she said. “Nothing.”

Beasley plans to spend much of her first year talking to people on campus and in the greater community about the difference Trinity has made in their lives and how they would make the institution better.

One of the things she says often is, “are we who we say we are?”

“Over time, and this is true for people and institutions, we should get clearer and clearer and clearer, about who we are and about being our authentic selves,” Beasley said. “Institutions have that too. Institutions have personality and authenticity [which] is really important to me.”

Out of all of Trinity’s values, Beasley wants to ensure things like intentional inclusion are present in everyday campus life. Working with Juan Sepúlveda, the President’s special advisor for inclusive excellence, has been invaluable, she said, for learning how diversity, equity and inclusion can be an important part of Trinity’s fabric.

“It’s just who we are,” Beasley said. “You stop having the discussions about whether [DEI work] is worth doing or not. It is who we are.”

This is not where Beasley thought she would end up when she first entered the world of academia. She studied at Vanderbilt during the Reagan presidency, arguably the first presidency to use television effectively. She watched this in awe, thinking maybe she would be a speechwriter, a campaign manager. A professor finally asked if she had thought about going to graduate school.

A hop, a skip and a jump down the line, Beasley is at the helm of a new adventure. Yet, she is always a student, always learning like the intellectually curious person she says she is. At the moment, this educational stomping ground is here at Trinity.

“I want to have the best and brightest and most capacious students who are up for the kind of education Trinity offers here now because that makes Trinity better in the future,” Beasley said. “That creates a network to support future students and it gives us the ability to think about, again, are we who we say we are? Have we created the kinds of students that are going to go out there and change the world? I think the answer is already yes, [and] I think it’s going to be an even more resounding yes.”

I am a senior French and Earth Systems Science double major from St. Louis, MO. When I'm not wearing my EIC hat, I am also a Chapel | Spiritual Life Fellow,...

My name is Sam (he/him) and I'm a photographer here with the Trinitonian. I'm a senior Communications and German double major from Austin, Texas, and...