Toxic South Asian beauty standards and social media

There has been upheaval within the South Asian community about social media personalities who are being recognized for the decolonization of South Asian beauty standards. One influencer comes to mind. Seerat Saini recently received criticism for her Allure feature: “Seerat Saini Is Decolonizing Desi Beauty, One Instagram at a Time,” when many claim that her Desi, light-skinned, North Indian experience isn’t single-handedly decolonizing beauty. Although she is creating some form of South Asian representation and is advocating for dark-skinned beauty, the argument is that influencers such as Saini should not be elevated for decolonizing beauty across the entirety of the South Asian community, especially since they benefit the most from toxic beauty standards. Seerat and many other influencers are leaving out forms of beauty found in many subcommunities such as dark-skinned South Asians, queer South Asians, South Indians and other indigenous South Asian communities.

The term “decolonization” has somewhat become a clickbait term that influencers have integrated into marketing their platform as “woke.” Instagram, TikTok and other platforms with algorithms that obscure racial prejudices put one-dimensional activists on the forefront, while other forms of activism that are unapologetic, loud and upfront don’t receive as much recognition and are constantly being trolled or censored. I had the opportunity to have honest conversations about the topic with three such activists – Sheerah Ravindren, Seema Hari and Natasha Thasan.

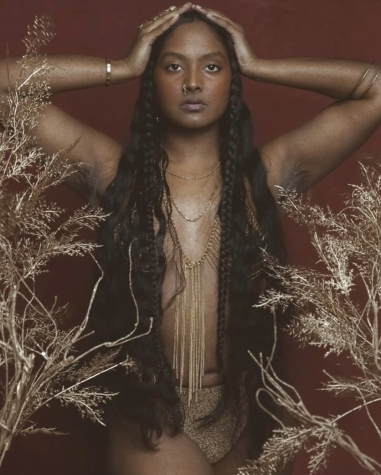

This conversation around South Asian marginalization isn’t “underground” in the sense that it is being overtly hidden. However, it is routinely excluded from homogenized South Asian social media spaces because it is not as easy to consume as more eurocentric forms of South Asian representation. When I think of Sheerah Ravindren’s platform, I think of daring, vibrant and confrontational – but never “easy.” Her feed is filled with evocative images of her body — her natural form, body hair, scars and skin color, which is apparently offensive to some, as she unfairly gets flagged on Instagram for going against “Community Guidelines,” for the same content white women and more “digestible” South Asian women post.

The discourse around the subject can be found in Reddit threads or TikToks, which are popular platforms, but it is often buried and people probably won’t stumble upon it unless they are actively searching for these conversations. For those outside of the South Asian community, the incongruities are not very apparent. They will probably believe the South Asian representation they see – the bhangra dancing, lehenga wearing, chaat loving culture of the North Indian diaspora – is how South Asian culture is observed universally.

—

Ravidren, a Tamil activist for Tamilian representation and body positivity, is most recognized for her appearance in Beyonce’s music video for her song “Brown Skin Girl.” She recognizes that even she, as a dark-skinned, Tamil individual of Sri Lankan descent, has her own privileges, such as some of her more eurocentric facial features or hair, that further stigmatized communities, such as Black communities, do not benefit from. She urges everyone to acknowledge their privilege openly and make active efforts to uplift marginalized beauty – online and offline.

“South Asian beauty influencers, whilst they claim they are celebrating non-Eurocentric beauty, need to understand how they are upholding white beauty standards through their own privileges of euro centricity,” Ravidren said. “As a non-Black person, I carry privilege over the Black community as a dark-skinned person but I have facial features and hair textures that are seen as palatable. My experience isn’t of someone that is the same complexion as me or has darker skin with non-eurocentric features. They’re going to have a different experience a further marginalized experience in terms of colorism. Every single experience that we have with oppression and privilege isn’t the same. […] I think that what I’d like to see in terms of decolonization in the South Asian community, number one, [is] that everyone needs to celebrate their differences, rather than trying to find a way to homogenize.”

Even the terms “South Asian” and “Desi” are byproducts of colonialism, a need to categorize everyone “cohesively” so it allows the privileged to comprehend the marginalized. Ravidren went on to share that she doesn’t identify with the term Desi since it “turmeric washes,” similar to “ whitewashing,” her Tamil heritage. She claims, “I’m Tamil before South Asian.”

“South Asian” only benefits those who are the most eurocentric, most digestible, most heteronormative and exhibit principles of more “palatable” exoticism that are found within the Western lens. Again, these are the South Asians that are revered by those outside of the community – the Priyanka Chopras and Aishwarya Rais of the world – the ones that are thin, tall, have big eyes, high cheekbones and lighter skin. It doesn’t help when more privileged South Asians, essentially anyone with heightened eurocentric aspects, claim to be “decolonizing” beauty standards for the entirety of the community. Claiming one form of South Asian expression as “common” results in marginalized South Asian communities, such as South Indians, dark-skinned North Indians and Pakistanis, the Eelam Tamil population of Sri Lanka or Indian communities of the Caribbean, being endlessly sidelined.

Seema Hari, a dark-skinned South Indian activist against colorism and casteism, featured in Vogue India, CNN and Times of India, puts it simply.

“Anytime you create a term for a group you’re trying to homogenize something that’s not necessarily homogeneous,” Hari said. “There are people within that spectrum of diversity as well. When you’re kind of by grouping them together, you’re trying to achieve something for a certain context. But for other contexts, that label might not be helpful at all because you’re actually, by creating a blanket term, you’re erasing some of their experiences.”

Natasha Thasan’s platform on Instagram, upon first glance, isn’t really the standard activism platform with infographics and essays. As a self-proclaimed Saree Architect, currently working on a saree clothing line, the focus of her page is on South Indian fashion and aesthetics. But what sets her apart from other “Desi” fashion accounts, is the way she authentically pays homage to Tamil fashion that is regularly left outside of the South Asian fashion space. She ardently educates herself and her online community on the rich history of fashion and culture found in underrepresented South Asian communities.

“I want it to become a point where [our culture] is just normalized, not like we’re begging for representation,” she said. Although she receives backlash from people within the South Asian community and outside, as many activists do, she continues with her artistry because she knows it’s part of a larger conversation. As a Saree Architect, a part of her platform is to inform her audience about the historical suppression colonialism has perpetuated onto indigenous clothing, such as characterizing it as “tribal” or “unclean.”

She shared that she sees many people commenting on her posts about cultural appropriation which bothers her, because she says, “it’s culture [that] was given to us. We’re so lucky to be born into [it]. Our ancestors and people before us have done all the cultural appreciation and have done all the work for us to enjoy it.”

When I asked why she keeps moving despite the hate, Thasan said, “It’s not about me. It’s about us. I’m just the mere instrument in this play.” It’s evident through Thasan’s words that the cause is larger than social media or any singular being.

And this backlash isn’t your run-of-the-mill cyberbullying. Ravidren and Hari also explicitly stated many of the trolling they receive are in the form of death and rape threats. Especially Ravidren, who grew up being characterized as “loudmouthed” and “troublesome,” carries that energy into self-appreciation and activism on her platform and has dealt with more threats than anyone should ever experience. They spoke about a time she advocated for minority Eelam Tamil genocide in Srilanka.

“It was the scariest 24 hours. I was literally nonstop harassed by Sri Lankan nationalists sending me death and rape threats and it was so scary,” Ravidren said. “They’re sending me pictures of dead Tamil people and I was genuinely thinking like, ‘oh my god, this is just me talking on my platform. Imagine what it feels like to be a Tamil person on the ground who’s speaking up against the government.’ You get killed. […] But I understand how big the platform that I have is, so if I know that enough people, especially from the communities that are oppressing us [and] following me, then I can then share the work of other people and direct people to those people so they can get exposed to more Tamil people who are having the conversations.”

Right then I realized that the conversations these activists were having on their platform, Ravidren, Hari and Thasan alike, were deeper than beauty and historical preservation — it was about systematic trauma from colonialism but also within the motherlands of these marginalized communities themself.

The inequity in beauty and color representation is continually upheld by South Asian communities that seem to be perpetually ridden with centuries of colonialist standards. That will always be a reality. But how do we, as individuals who more systematically benefit from the power structures in society and social media — especially in beauty, capitalism and colorism — stand as allies for those that don’t carry the same privilege? I asked all three activists the same question, and the answer seems pretty simple: be aware of our privileges. We must continue to educate ourselves and challenge our internal biases.

“If you’re talking about colorism, we have to center the most marginalized people,” Hari said. “If you’re still centering the people that are most adjacent to whiteness, then you’re not really creating South Asian representation […] so when you’re coming through it as an ally, I always think about de-centering yourself and making it about the other person and thinking about what you can do for them.”

Hari is right. If we continue to only highlight activism efforts for the most normalized-adjacent individuals, the most privileged, the ones with the most access to capital and opportunities, they are the ones that will continue to thrive, while others remain on the margins.

Hello! I am a junior English and Business major with a minor in creative writing. As an opinions columnist, I’m passionate about exploring anthropological...

I am a senior Art and English double major from San José, California. I also have an accidental Medieval and Renaissance minor that I picked up through...